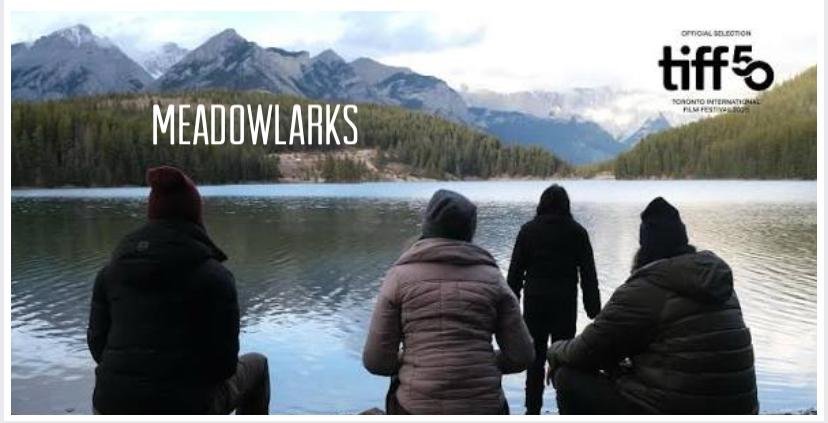

TIFF 2025 Review: Meadowlarks “A Gentle Reckoning Carved in Quiet Spaces”

“Quietly powerful — a film that lingers in the heart.”

Some films roar, and movies that whisper. Meadowlarks belong unmistakably to the latter

category. Directed by Cree filmmaker Tasha Hubbard in her narrative feature debut, this is a

movie that asks you to slow down, sit with absence, and feel the spaces between the words as

deeply as the words themselves.

Inspired by Hubbard’s acclaimed documentary Birth of a Family, Meadowlarks tells the story of

four Cree siblings. Anthony (Michael Greyeyes), Connie (Carmen Moore), Marianne (Alex Rice),

and Gwen (Michelle Thrush), who were separated as children during Canada’s Sixties Scoop,

reunite decades later for a long weekend in Banff. The goal is simple: to meet. But what unfolds

is layered: grief, confusion, longing, hope, and the strange awkwardness of trying to be siblings

when you never really were together.

An Emotional Story, Painted in Stillness

From the film’s start, director Hubbard treats the setting in Banff as part of the story and its

characters. The mountains, the quiet rental house, are more than a backdrop for a reunion of

four lost family members. It becomes the emotional terrain of the siblings’ journey. The vast

peaks and silent woods echo what’s been missing: the cultural roots, the shared laughter, the

childhood games. But the same landscape also suggests possibility. There is room to breathe,

to confront, to heal.

Cinematographer James Klopko frames long shots of the characters standing in lobbies, gazing

out windows, and hiking trails. These aren’t action beats; they are pauses. In those pauses, you

feel the passage of years, the weight of separation, the distance of memory. The film trusts

space, and in doing so, it trusts you.

Hubbard wisely avoids heavy dramatics, opting instead for the small: a coffee poured in silence,

a sibling glance exchanged without comment, the awkwardness of being in each other’s lives

for the first time. It’s in these small beats that Meadowlarks finds its power.

The Cast: Wounds, Words, and Resonance

Greyeyes, Moore, Rice and Thrush give the film its living heart.

Michael Greyeyes’s Anthony is at once gentle and haunted. He’s the one who tried to hold

on, who attempted to be content, but you can see the missing years etched in his face.

Greyeyes shows both vulnerability and a quiet strength. Anthony’s attempt at “everything is ok”

cracks early, and Greyeyes lets you feel the fracture.

Carmen Moore’s Connie is the one who plans the retreat, tries to fill the air with rituals and

expectations, and simultaneously carries a protective shell. Moore plays the sibling who holds

the agenda, in some ways comforting, but also controlling, and that complexity is vital.

Alex Rice’s Marianne, raised overseas, is the outsider among siblings. Her joy and confusion

are easy to empathize with. Rice imbues Marianne’s desire with a luminous quality: to belong,

reconnect, and understand what it means to be “home.”

Michelle Thrush’s Gwen grounds the ensemble. Her past struggles, her strength, her refusal to

be sentimental alone. Thrush weaves all that in quietly, and it stays with you.

Together, they are convincing. The truism you sometimes see in listings is that they look like

siblings. But more importantly, they feel like siblings who never knew each other but are trying

together.

Story and Structure: What Works, and What Hangs in the Air

Meadowlarks is structured for reconciliation rather than revelation. There is no “big secret drop”

moment. Instead, the film unfolds through revelations of daily living: shared meals, sibling

banter, therapy-style conversations, and the odd ritual that arrives too early, too late.

This is both its strength and, for some viewers, a hesitation. Some critics have noted that

certain scenes lean more toward exposition than genuine dialogue. For example, the siblings

sometimes speak in terms of “I feel” and “I was taken” rather than the messy halting of real

people. At times, the film feels more like a stage piece than a film, with a dozen conversations

unfolding in one house over the course of a weekend. But I found that it suited Hubbard’s

intention: this is a film about reconnection, about making space for words unsaid and years

lost. The directness of the dialogue reflects the urgency of reclaiming the story.

What I kept returning to was the film’s refusal to tie things up neatly. There is laughter, tears,

awkwardness, silence, and nothing wraps in a tidy bow. The missing sibling who doesn’t attend

is mentioned but not fully dramatized. Some backstories are sketched, not fully drawn. But

perhaps that’s the point: the siblings themselves don’t have all the answers yet, even as they

come together. Healing doesn’t present a checklist. Meadowlarks understands that.

Themes: Identity, Trauma, and the Work of Belonging

The Sixties Scoop is not a context but something that is woven into the fabric of Canadian

history. The film’s director, Hubbard, made comments that Indigenous stories have often been

treated as “window-dressing,” and Meadowlarks is working to change that view. She refuses to

define herself as a victim; instead, she allows for complexity. The siblings are survivors, yes, but

they are more than that. They are personalities shaped by absence, language loss, and cultural

erasure, yet they still desire to connect.

The film angles expressed siblings’ yearning: what happens when you are raised in a family that

isn’t yours, in a culture that isn’t yours, and told you belong, but don’t feel it? And what

happens when you finally meet the people you were supposed to grow up with, decades later?

Meadowlarks lets you live through that.

In one scene, the siblings participate in a smudging ceremony led by the elders. None of them

knows exactly what to do—but they commit. That moment engraved itself in me. It is symbolic

of what can’t be reclaimed: language, childhood, shared rituals—but also of all they can claim:

presence, choice, each other. The film is “moving and emotionally resonant,” noting how it

frames hurt and reclamation side by side.

The Emotional Experience at TIFF

At TIFF 50, Meadowlarks appeared in a crowded program of premieres, but it held its space

quietly and compellingly. I saw sat in stillness; the recessional moment felt like a communal

exhale. Some critics lauded the film for elevating Indigenous stories to mainstream drama;

others noted structural issues, but almost all agreed that the subject matter demands attention.What lingered with me was not a single scene of confrontation, but the accumulation of

glances, passings in hallways, unspoken pain. There is no dramatic moment of revelation.” Still,

there is a moment near the end—where the siblings mount a mountain trail together, silent,

each step echoing the distance they’ve travelled internally. That sequence will stay with me.

Final Verdict

Meadowlarks are not perfect. It sometimes teeters between ceremonious drama and direct

emotional statement. Some scenes feel more scripted than spontaneous. But it is honest. It is

intimate. And in the way it trusts us to feel the silences, the mis-steps, the hopeful glances, it is

generous.

Tasha Hubbard has not only dramatized the story of the Sixties Scoop, but also doesn’t just

dramatize it. It invites the viewer into the aftermath. It’s a film about siblings, yes, but also

about legacy, about belonging, about the work of piecing together what was taken. Watching it,

I felt the weight of what had been lost; leaving it, I felt the possibility of what was still ahead.

In a festival filled with noise, Meadowlarks whispered—and I leaned in. For its heart, its care, its

willingness to sit in the ache of reconnection.

“Meadowlarks doesn’t ask to be cheered—it asks to be heard.”