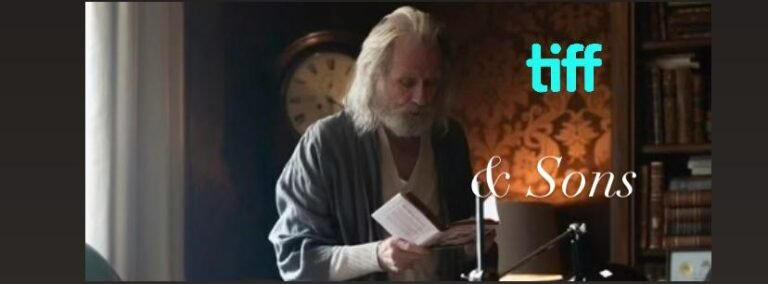

Rental Family

Rental Family — TIFF 50 “Sometimes the people you hire become the family

you need.”

If Rental Family were a song, it’d be a whisper in a crowded room, subtle, slow, and full

of longing. Directed by Hikari and starring the emotionally resonant Brendan Fraser,

the film premiered at TIFF 50, occupying that uneasy space between performance and

reality.

Fraser plays Philip Vandarploeug, an American actor adrift in Tokyo, whose loneliness

leads him to a strange job: playing roles in people’s lives. From a mourner at funerals to

a faux father, and even an actor-journalist for an aging filmmaker, Philip’s assignments

start as detached work but slowly pull him into the lives of the people he’s pretending

to care about. The lines blur. And Fraser? He carries it all with gentle sincerity, longing,

shame, awkwardness, and hope.

Visually, Rental Family captures Tokyo’s heartbeat. Neon lights, crowds, narrow alleys,

sprawling apartment windows. The city feels like both a refuge and a cage. Philip’s

loneliness is highlighted by shots where he’s small against the skyline, distant from life,

watching through windows. It’s beautiful but fragile. The score, by Jónsi and Alex

Somers, surrounds the emotion without overwhelming it; woodwinds, piano, and light

strings punctuate moments of silence. It allows you to feel what Philip doesn’t yet know

how to put into words.

Supporting characters add depth to the film’s heart. Shinji, played by Takehiro Hira, is

the CEO (Rental Family) who first hires Phillip, an American actor, into his unusual

business, which provides “rental” family members and companions to clients in need.

Initially impressed by Phillip’s performance at a fake funeral, Shinji offers him a job,

seeking a “token white guy” for specific roles. As Phillip becomes emotionally invested

in his work, Shinji’s detached professionalism creates a sharp moral contrast between

them, turning him into both a mentor and a catalyst for conflict as the film questions

the ethics of fabricated human connection.

Mari Yamamoto’s Aiko has a quiet bitterness shaped by her own “roles” in this

economy of affection. Akira Emoto’s performance as Kukio, the aging film actor,

gracefully evokes a profound sense of longing and balances dignity with a sense of loss.

Emotive scenes with Fraser and Akira, as they try to fulfill a last request. Shannon

Gorman, playing Mia (the child who believes Philip is her birth father), brings a tender

innocence, the kind that fractures easily when she learns (or doesn’t) what’s real and

what isn’t in her life. These connections don’t erase Philip’s existential wandering; they

only deepen it.

What Rental Family does best is show that even pretend roles can feel desperately real.

The ethical edges are always present: deception, emotional labour, and loneliness for

hire. Yet the film rarely delves fully into moral judgment. Hikari seems more interested

in the spaces between people, in how we perform love when the world won’t offer it

otherwise. Watching, you wonder: is love because of what’s real, or what’s felt?

But the film isn’t perfect. Sometimes, its gentleness becomes too polite, its sentiment so

carefully curated that some scenes feel like highlight reels rather than fully lived

moments. Certain arcs—Philip’s inner history, his motivations beyond loneliness—are

hinted at but never fully explored. The movie occasionally wavers between charm and

cliché.

Still, what stays with you isn’t the flaws, it’s the ache. Rental Family doesn’t offer easy

answers, but it gives something rarer: compassion. It reminds us that “family” doesn’t

always come from blood, and sometimes the roles we play can lead us toward being

seen.

By the end, you’ll find yourself rooting for Philip not because he’s pretending well, but

because somewhere in his performance, he begins to believe he might belong. TIFF 50

needed a movie like Rental Family: quiet, messy, hopeful. “When pretending

becomes home, the truth becomes the enemy.”