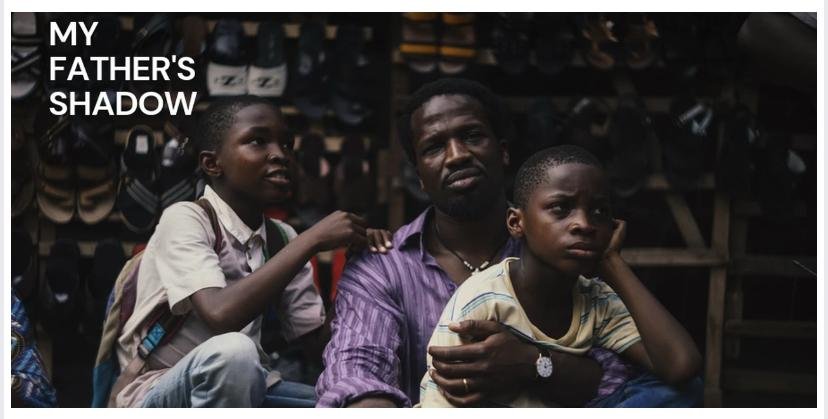

TIFF 50 My Father’s Shadow Review

My Father’s Shadow is a film that quietly creeps up and then surprises you with how

deeply it resonates. Directed by Akinola Davies Jr. and co-written with his brother Wale

Davies, this debut feature takes place over one tense day in Lagos in 1993. Two

brothers (performed by siblings Godwin Chiemerie Egbo and Chibuike Marvellous Egbo)

are led by their father, Folarin (who delivers a powerful performance by Ṣọpẹ́ Dìrísù), as

he tries to retrieve his unpaid wages from his employer and explain to his sons why he

has been so absent. Against the backdrop of cancelled elections, hints of military

crackdowns, and a nation teetering between hope and collapse, the film weaves

something tender and heartbreaking—making it all the more powerful through its quiet

strength.

What hits hardest is how the film anchors itself in the emotional truth of absence.

Folarin returns to his boys unexpectedly. They only know him in fragments: the man

who’s away in Lagos, the authority figure, the one who sends money, the one who isn’t

home. And here he is, on this day—their day—with the boys suddenly in tow. Davies Jr.

uses this setup beautifully: the boys aren’t just observers of their father’s world—they’re

entering it, watching him struggle, fail, and strive, exposing himself to them in a way.

Through their eyes, we ask the question: If someone works hard, shows up, but

still is gone—is that love? The film doesn’t give easy answers. At one point, the

younger son asks: “If you say that you love us and God loves us, then does that mean

people who love us are always far away?” That line moved me. Because it holds the

ache of wanting closeness, but knowing how distance becomes a form of presence and

absence becomes its own kind of story.

Dirisù’s portrayal is subtle but layered. He’s not a perfect father, and the film allows

space for his flaws—his fatigue, his compromises, the weight of his job, and the burden

of being a provider in a country where so much is stacked against the working man.

You watch the boys try to read him, to love him, to challenge him—and you feel them

growing up in that process.

The setting is more than wallpaper. Nigeria in 1993 wasn’t simply a backdrop—it was a

living, breathing part of the story. The annulment of the election results, the eruption of

civic protest, the heavy hand of military rule—they’re never overwhelming the intimate

story. Still, they pulse beneath it, like a slow drumbeat announcing that even as this

family goes through its pain, the country is going through its own.

There are moments of vivid, textured detail—bus rides jammed with passengers, half-

filled trucks, petrol queues, crowds moving in frustration. The film guides the boys (and

us) through a physical journey from the village to Lagos, as well as an emotional

journey from innocence to an uneasy maturity. Cinematographer Jermaine Edwards’s

lens is gentle but alert: the shift from calm rural life to the jittery, electric city mirrors

the boys’ internal shift.

And yet, some critics point out that the political context is delivered rather directly,

almost too clearly for a film that wants to stay told from the boys’ viewpoint. The film

sometimes pauses to remind you of Nigeria’s political crisis, rather than letting you live

the tension purely through character.

But in a film so personal, perhaps the tradeoff is understandable: you want to know the

stakes of what the father is up against, so the story occasionally steps outside the boys’

perspective to provide a wider frame. It might not always be perfect, but it doesn’t

derail the emotional core.

Davies Jr. doesn’t go for big fireworks. His style is deft, restrained, attentive. The real-

life brothers (Egbo & Egbo) are beautifully cast; they have the kind of chemistry that

only siblings can have, and it brings a natural ease to many of their scenes: their

banter, their minor quarrels, their wonder at their father’s world.

And when he lets the camera linger, on the father’s brow, the boys’ eyes watching

something they can’t yet interpret, a flock of birds swirling overhead, you feel the film

settling into its emotional marrow. One review describes it as a “love letter to an absent

father” and “a slow recognition” of someone you thought you knew.

There’s a strong thread of memory and how memory works. Not as neat a narrative but

in shards, in smells, in moments of epiphany. The film captures how childhood

constantly tries to map adulthood, and how, sometimes, the mapping is wrong, yet still

matters.

If I have any nitpicks, the ending felt abrupt to me. The emotion had built steadily, and

the final turn, while effective, left me wanting a little more space to breathe and

process. Additionally, the political context, while integral, sometimes feels slightly

unbalanced with the personal story—and for me, it is the individual who truly soars.

Critics have pointed out that the film “plays things safe”.

For so many reasons, this film matters. The first Nigerian film to be officially selected

and to be presented as part of the Cannes’ Un Certain Regards section. This selection

marks a new shift in global cinema, signalling that Nigerians are now telling stories from

Nigeria. The Davies brothers are part of the latest shift. They’re making global cinema,

but rooted in specific lives, places, and griefs.

Beyond that milestone, it’s a film that talks about what so many of us know: growing up

in the gap between what a parent does and what a parent is; the burden of sacrifice;

the longing for closeness; the quiet recognition that someone you loved is complicated,

flawed, but still worth loving. It’s the kind of story that doesn’t need grand gestures; it

works in the small ones, the glances and silences. And for a debut, that’s ambitious.

My Father’s Shadow is a quietly powerful film. I watched it, not expecting to be

moved this deeply, and I found myself thinking about my own father’s absence, time,

and what it means to come home to someone you barely knew. It bills itself as “one

day” in the lives of a father and his sons, but that single day carries years of yearning.

Performance-wise, it shines. Directionally, it’s confident. Story-wise, it resonates. Yes,

there are structural moments that feel too tidy, and yes, some of the political exposition

could have been more integrated; however, none of that diminishes the heart of the

film.

In short: if you see only one film at TIFF or this award season, make it this one. It will

change how you think about love, family, and the making of memory. It’s a

homecoming in motion.